Alessandro Manfrin

Alessandro Manfrin “Bomboniera” at Gian Marco Casini Gallery, Livorno

Alessandro Manfrin "Bomboniera" at Gian Marco Casini Gallery, Livorno

Le forme fragili delle cose. Alessandro Manfrin “Bomboniera” Gian Marco Casini Gallery / Livorno

Bomboniera. Alessandro Manfrin

text by nadir daily

it

‘Bomboniera’ – dal francese bonbonnière, scatola di dolcetti, bonbon – nella lingua italiana ha preso un significato specifico. È un piccolo oggetto regalato in occasioni importanti, racchiuso in scatole di forme diverse. Spesso associata al bianco e a una situazione intima, soffice, delicata – con il tempo si immobilizza, chiusa in credenze improbabili, sospesa in una quiete inefficace. Eppure continuiamo ad accoglierle, a collezionarle, fino a riuscire a disegnare una mappa immaginaria – bonbon malinconica – di persone e luoghi. ‘Bomboniera’ di Alessandro Manfrin si insinua in questa condizione di deriva di ciò che rimane.

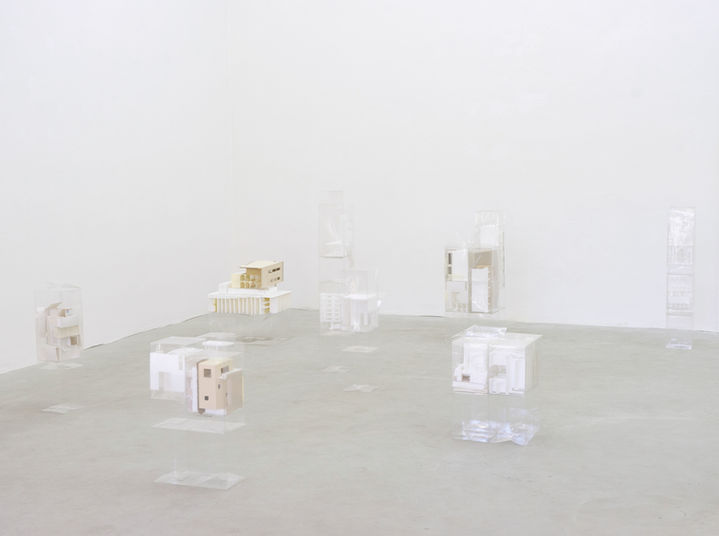

È una questione di materiali – ma più a fondo – di un’impervia discesa nelle abitudini dell’umano. Cartone, polistirolo, nastro adesivo, PVC, cellophane, carta velina, confezioni usate, cerotti. C’è qualcosa di profondamente tenero nel rovistare tra gli scarti. Come se ogni oggetto trovato, ogni pezzo di plastica, carta velina o nastro adesivo, conservasse l’umore di qualcuno che lo ha toccato, guardato, dimenticato. Materiali usa-e-getta – presi da vite altrui – diventano monumenti brutalisti di una città invisibile. Come Score (2025), una distesa di modellini architettonici che in una linea sospesa immagina un orizzonte instabile di polistirolo, legno e cartone. Forse è questa la città che desidera, e ce la sussurra.

Il candore rilasciato dalla galleria che a sua volta diviene forma-bomboniera è una somma di complessità, una ricerca irriverente tra reliquia e dono, tra rifiuto e affezione. E rivela il tratto istintivo del lavoro di Manfrin: la composizione – cioè l’assetto grammaticale del suo fare – segue quasi sempre la sensazione frammentata e contrastante dell’iperconsapevolezza. La sua pratica è tesa verso una leggerezza eterea fatta di segni scomposti, quotidiani, social disfunzionali. Il punto di riferimento non c’è, o meglio: si frammenta in più direzioni non allineate. Michel Foucault, nella sua definizione di eterotopia, afferma che ci sono paesi senza luogo e storie senza cronologia; semplicemente perché non appartengono a nessun spazio. Dov’è quindi la direzione?

Bomboniere (2025) è una serie di sculture grattacielo che suggerisce verticalità, forse per il desiderio di rompere il cielo, esserne parte, essere sopra le parti, e acquisirne una porzione. È come se questo soffice abitare fosse ovattato da uno strato di patina bianca, appiccicosa. Una solidità maneggevole e quotidiana – forse una gomma da masticare – che tiene insieme una contemplazione infastidita e paralizzante, l’horror vacui. La forza del vuoto risiede proprio nell’atto di non aggiungere, come nella torre di Babele, mai completata e destinata a uno stato di rovina. La scelta di non costruire e costruire appunto il vuoto è ciò che genera mancanze tali che la forma stessa può evocare delle volte un senso di angoscia.

Nel cuore di questa riflessione si inserisce Untlited (elevator) (2025), un loop video di 2 minuti e 52 secondi scanditi da un acufene che pervade lo spazio. Sopra, sotto, dentro e fuori una vibrazione incorpora un rumore bianco. Il vuoto diventa qui abitabile, in uno stato consolatorio in cui ti osservi cadere, come se fossimo in una città sospesa disegnata da Aldo Rossi, dove la solitudine della metropoli si fa spazio condiviso di chi osserva e cammina. In continuità con questa atmosfera sbucano i Pimple patches (2025), cerottini color pastello per la cura della pelle attaccati a lampade usate e sfere di vetro sporco, che rimarcano in questa costellazione di tentativi, la voglia di guarigione e di un’attenzione delicata ma imperfetta. Le sfere rotolano nella frammentarietà architettonica di plastica leggera, vetro polveroso, polistirolo – le immagini si aggregano in forme che sembrano giocattoli e al tempo stesso reliquie, come resti di una civiltà che ha imparato a sognare tra i margini. È un brusio costante, un rumore bianco che attraversa le cose e le tiene insieme, senza mai risolversi, e in questo flusso Manfrin costruisce grumi di stati d’animo nei quali ci butta in mezzo, cercando squarci di luce quotidiana. A volte, è una luce quasi spaventosa, altre volte può diventare la nostalgia di un posto dove non siamo mai stati.

en

“Bomboniera” – from the French bonbonnière, meaning a box of candies or bonbons – has taken on a specific meaning in the Italian language. These small objects are gifted on special occasions, enclosed in boxes of various shapes. Often associated with white and an intimate, soft, delicate feel – with time they become immobilised, put away in unlikely cupboards, suspended in an ineffectual stillness.

And yet we keep accepting them, collecting them, to the point of being able to outline an imaginary map – melancholy bonbon – of people and places. Alessandro Manfrin’s “Bomboniera” wanders into this adrift state of what remains.

It’s a question of materials – but more deeply – of an arduous descent into the habits of humanity. Cardboard, polystyrene, tape, PVC, cellophane, tissue paper, used packaging, bandages. There is something deeply endearing about rummaging through scraps. As if every object found, every piece of plastic, tissue paper or piece of tape held the mood of someone that touched it, looked at it, forgot it. Disposable materials – taken from other people’s lives – become brutalist monuments of an invisible city. Like Score (2025), an expanse of architectural models that, in a suspended line, envision an unstable horizon of polystyrene, wood and cardboard. Perhaps this is the city it longs for, and whispers to us.

The whiteness emanating from the gallery, which itself turns into a sort of bomboniera – is a union of complexities, an irreverent exploration somewhere between relic and gift, between reject and affection. And this reveals the instinctive character of Manfrin’s practice—that is, the grammatical structure of his work—which almost always follows the fragmented, conflicting sensation of hyperconsciousness. His practice aims for an ethereal lightness made of disjointed, mundane, dysfunctional social signals. There is no point of reference, or rather: it is fragmented in multiple non-linear directions. Michel Foucault, in his definition of heterotopia, states that there are countries without a place and stories without chronology; simply because they belong to no space. So where is the direction?

Bomboniere (2025) is a series of sky-scraping sculptures that suggests verticality, perhaps because of its desire to break the sky, be part of it, be above its parts, and attain a portion of it. It’s as if this soft dwelling were muffled by a layer of white, sticky patina. A convenient, everyday solidity – perhaps chewing gum – that holds together an irritated and paralysing contemplation, a horror vacui. The power of the void lies precisely in the act of not adding, like the Tower of Babel, never completed and destined to ruin.

The choice not to build, and indeed to build emptiness itself, creates absences such that the form itself can sometimes evoke a sense of anguish.

At the heart of this reflection is Untlited (elevator) (2025), a 2-minute-52-second video loop with a tinnitus-type hum that invades the space. Above, below, inside and out, a vibration incorporates white noise. Here, the void becomes inhabitable, in a comforting state where you watch yourself fall, as if we were in a suspended city imagined by Aldo Rossi, where the solitude of the metropolis becomes a shared space for those who observe it and traverse it. In continuity with this atmosphere there are the pimple patches (2025), pastel-coloured skincare patches stuck on used lamps and dirty glass spheres, which underscore, in this constellation of attempts, the desire for healing and delicate but imperfect attention. The spheres roll around in the architectural fragmentation of lightweight plastic, dusty glass, polystyrene – the images come together in shapes that seem simultaneously like toys and relics, like the remains of a civilisation that has learned to dream in the margins. It’s a constant buzz, white noise that passes through things and holds them together, without ever resolving itself. And in this flow, Manfrin constructs clusters of states of being, which he throws us into, searching for glimpses of ordinary light. At times, it’s an almost frightening light, at other times it can become nostalgia for a place we’ve never been.

Translated by Rachel Moland

(it) di20in20 [02]: Alessandro Manfrin e Nadir Daily. @radio spugna 🧽

(en) I (never) explain #170 – Alessandro Manfrin, ATP DIARY

Hard work soft dreams

Mi trasferisco a Milano nel 2019. Fin da subito, e in maniera piuttosto ossessiva, comincio a fotografare i materassi che vengono abbandonati sulle banchine delle strade. Tutto nasce da un’attrazione puramente formale, penso a questi oggetti totalmente devoti al riposo, materiali che hanno passato la propria intera esistenza supini e immobili nelle nostre camere da letto il cui unico sforzo richiesto è di farsi architettura della notte. Incontrarli per strada li rende giacigli stanchissimi esposti allo sguardo voyeuristico del mondo, dolci sudari di sconosciuti in attesa che l’Amsa li porti via. È materia bianca e intima, d’improvviso sputata nello spazio pubblico e costretta a posizioni scomode sull’asfalto.

Spesso penso al mio lavoro come a un gioco le cui regole consistono nel rintracciare le cicatrici e gli effetti collaterali di una città nevrotica. In questo senso, i materassi usati sono sinceri e spietati nel mostrarsi nudi, con le proprie geografie disegnate da macchie e aloni. Dermatiti di cotone.

Parallelamente inizio a lavorare alla mia tesi su Robert Smithson. In un testo pubblicato su Doppiozero scritto da Riccardo Venturi che titola ‘Roma, 15 ottobre 1969 / Robert Smithson: “Let Asphalt Flow!”’ leggo:

Mi rendo conto che sono attratto da tutto ciò che va verso il basso, che va nel senso contrario dell’elevazione della scultura classica o di Manhattan, ma questa è un’altra storia. Un’adesione incondizionata alla gravitas portata a un punto di non-ritorno, a un punto irreversibile, quello dell’entropia. Asphalt Rundown sarà una scultura che cade; l’ultimo capitolo di una storia della scultura cominciata con le Deposizioni; il mio omaggio estremo all’arte di Michelangelo.

Comincio a scuoiare con un taglierino i materassi ricavando così delle sorta di lenzuola che diventano drappi appesi al muro del mio studio. Sculture che cadono per usare le parole dell’articolo su Smithson. Trofei di caccia, una caccia a un tesoro che è sotto gli occhi di tutti. Sono monumenti alla vita vissuta, psicografie surrealiste.

Sono molto affezionato a quei lavori che nascono quasi da sé, in cui il mio intervento è minimo e impercettibile. Al principio di questo lavoro c’è un lungo processo di ricerca del materiale e di cambio di forma, ma una volta ottenuto il rettangolo di stoffa è come se tutto quello che si poteva fare sia stato fatto. In questo senso mi interessa stare dietro le quinte, fare il minimo indispensabile. Non penso sia un gesto di scarsa generosità, ha più a che vedere con lo sguardo, è come se lavorassi più con gli occhi che con le mani. Il mio lavoro è prima di tutto trovare e riconoscere dei materiali evocativi e in un secondo momento agire in sottrazione per mezzo di una serie di scelte e decisioni formali.

Il titolo Hard work soft dreams, come spesso accade nei miei lavori, nasce precedentemente alla realizzazione della opere. Mi interessa come il titolo evochi uno slogan tipico della retorica del capitalismo e del successo personale. Un invito al lavoro duro e a fare sogni morbidi.

Cloud traces

text by Simone Molinari

it

Una certa esplorazione superficiale, una peregrinazione visiva e viscerale, placida osservazione di pelli e pellami. Perché la superficie è immediata ostentazione di qualcosa le cui regole non sono necessariamente date a sapere, anzi. Ogni superficie vive nel metamorfico tempo del miraggio e di sbornie formali.

Superfici di nuvole, superfici nuvolose. Superfici di ovatta, superfici pelose. Superfici transitorie e transitive, le cui qualità indefinite si riversano nel paesaggio quando scendono a valle e si trasformano in nebbia. Nebbia e nuvola, due paradigmi del pensiero, tra ottusità e lucidità, smog concettuale e fumettistica frase sospesa su un volto rimuginante.

E ancora, superfici riflesse su superfici riflettenti. Vetri che, sotto la carezza di leggere nuvolette milanesi, si fanno specchi. Palazzi che, davanti al passare monotono e grigio di un cielo economico, si fanno cornici.

La tempesta dov’è? Si attende un cielo buio e nero, come in certi quadri di paesaggio olandesi, figli della stessa bramosa fame borghese che ci ha regalato le citylife del mondo intero. Citylife, la vita della città, dove passa il sangue e pulsa il battito, alito sommesso e salatissimo sudore; dove il respiro del capriccioso e sognante mondo finanziario si condensa in nuvolette dirette, chissà dove.

Si sviluppa un arcipelago di macchie, sudori, trascorsi liquidi e malconci sul bianco mare della notte. Si naviga per questo oceano come naufraghi, arresi alla logica dell’incontro inaspettato. Regali anonimi e impersonali che tracciano un percorso di vite e dolori; i rigurgiti della città ne compongono il sudario. Pullulano le vie di questi pallidi fantasmi, accovacciati in silenzio; dolcemente si ripiegano in attesa di mani che, in altrettanto silenzio, li portino via.

Ogni scontrino è il prodotto di un modesto contatto tra carta e calore, piccola magia chimica, scrittura termica. Registrazione fisica, biologica quasi, di uno sbalzo di temperatura; pensiamo le centinaia di migliaia di questi foglietti dispersi per strada come a un frammentario termometro del clima umorale della città. Desideri, paure e ossessioni mappate da tiepide impronte di transazioni quotidiane.

“Niente cambia forma come le nuvole, se non le rocce” scriveva Hugo. Pelle d’oca urbana, il grigio sfilacciamento di mura e pareti. È la periodica muta della città che cambia e sale, lo spettacolo di una infinita colata di cemento che riempie, panna minerale, la pancia dei cantieri. Non è sazia la metropoli, il prurito persiste, nervoso, e i palazzi che grattano il cielo provano invano a saziarne i capricci.

Risate, suoni metallici e duri, graffianti. Affanno e mugolio, musica che ascende dalle viscere oscure di bestia. La città si rivela organismo, e l’artista, il cui sacco è pieno di tesori e piccoli miracoli, ne setaccia le carni. Magico e chirurgico, dissezioni calcolate sotto lo sguardo nervoso da flâneur.

Il tubo è un lavoro di metonimia, congiunzione meccanica e retorica tra il minimo e il tutto, tra il micro e il macro. Relitto metallico sgusciato tra le maglie dell’amministrazione metropolitana; spina dorsale, costola, ossicino cavo o cartilaginoso. Stretta gola, la cui particolare intonazione rimbomba l’eco dei gutturali concerti che animano il torace della città.

Il cielo perde tinta, si spiaccica a terra e sul muro il suo colorito celeste. Foglio brillante e vivace, squarcio irreale nel pastoso paesaggio milanese. Blueback: schiena azzurra, torso turchese, incarnazione cartacea; sprazzi d’astrazione fanno breccia nella politica figurativa che tiranneggia per la città. Perchè visione corrisponde a pubblicità: la forma sarà prodotto, economicamente riconoscibile.

Ma sotto al peso del tempo, del passare delle mode, del cambio di stile e di stagione, la pesante pelle si sgretola e irrigidisce. Così il profitto perde forma e dall’epidermide sbuca una informe e vera malinconia, amorfa contemplazione. È la bramosia che si sgonfia e ammoscia, è il ritorno di un romantico, vago, nuvoloso desiderio.

en

A certain kind of superficial exploration, a visual and visceral wandering, a placid observation of leathers and skins. Every surface is the immediate display of something that’s rules are not necessarily accessible or known. The surfaces exist in a metamorphic vacuum: a space of mirages and drunken forms.

Surfaces of clouds, cloudy surfaces. Soft surfaces, hairy surfaces. Fleeting and contagious

surfaces, whose indefinite qualities spill over the landscape as they descend into the valley and turn into mist. Thought-shaped clouds, between obtuseness and lucidity, conceptual smog and cartoonish words floating on a preoccupied head.

Reflected surfaces on reflective surfaces. Glasses that become mirrors under the caresses of elegant, Milanese clouds. Buildings that frame the monotonous, gray passage of a dull sky.

Where is the storm? We are left waiting for the dark, black sky found in Flemish landscape paintings, products of the same greedy, bourgeois, hunger that has given rise to the many Citylifes of the world. Citylife, the life of the city, where the blood flows and the pulse beats, weary sighs and salty sweat; where the breath of the capricious and dreamy financial world condenses into small clouds headed, no one knows where.

An archipelago of traces of stains, sweat, and liquids unfolds on the white territory of the night. One navigates this ocean like a castaway, abandoned to the logic of unexpected encounters. Anonymous and impersonal gifts trace the paths of different lives and their sorrows; the shroud of the city is decorated by its nocturnal regurgitations. These pale ghosts crouch quietly on the street floor, gently slumped, waiting for hands that, silently, will take them away.

Each receipt is the product of a modest contact between paper and heat, a tiny chemical magic: thermal writing. Physical, biological records of temperature change; these hundreds of thousands of notes scattered on the streets divulge a fragmentary thermometer of the city's mood. Desires, fears, and obsessions are mapped by the tepid footprints of everyday transactions.

“Nothing changes form so quickly as clouds, except perhaps rocks”, wrote Hugo. Urban goosebumps, the depressing unraveling of walls. The city’s periodic shedding of its skin changes and rises: an endless flow of cement fills new holes whilst old, concrete mountains crumble. The metropolis is never sated, its uneasy itch persists, as each new skyscraper tries in vain to wet its voracious appetite.

The sound of laughter mixed with the harsh, metallic groans of the underground. Wheezing and thundering music rises from the dark bowels of the beast. The city is revealed as an amorphous organism, and the artist, whose bag is filled with treasures and small miracles, carefully examines its flesh. Magical and surgical, calculated dissections are performed under the nervous gaze of the flaneur.

The metal tube is a metonymy, a mechanical and rhetorical conjunction between the smallest part and the whole, between the micro and the macro. An iron wreck that slipped through the net of the urban administration; a spine, a rib, a hollow or cartilaginous bone. A narrow throat, whose peculiar intonation echoes the guttural sounds that animate the city's chest.

The sky releases its color, it splashes on the ground and on the walls. Bright and vibrant, the blueback slices into the mellow, Milanese landscape. Blueback: turquoise torso, papery flesh. On each billboard, flashes of abstraction break through the figurative politics that shape the city.

Under the weight of time, the passing of fashions, the changing of styles and seasons, their heavy skins crumble and stiffen. Profit loses its shape and from the metropolitan epidermis emerges a shapeless and true melancholy, a new amorphous form of contemplation. It is the deflation and softening of capitalist lust; it is the return of a romantic, vague, and cloudy desire.

(it) Stare con l'immagine. Conversazione con Alessandro Manfrin.

Editoriale di Francesca Brugola per Balloon project. Marzo 2024.

Se si dovesse individuare una struttura ricorrente nei lavori di Alessandro Manfrin, sarebbe la dicotomia, possa questa intendersi come una tensione tra architettura e rovina, sogno e malattia, pittura naïve e immagini di guerra.

Senza titolo (Tonante veduta) è un lavoro di found footage. Le clip sono state prese da un canale YouTube trovato sull’applicazione Warmap, utilizzata dai reporter per segnalare zone di guerra attiva ad altri colleghi, e successivamente montate da Manfrin.

Sono clip che mostrano i cieli del Donbass bombardato, e risalgono ad attacchi precedenti a febbraio 2022, quando la Russia entra militarmente in Ucraina. Qui si riconosce il momento in cui la fruizione delle immagini di guerra da particolare diviene diffusa, e di conseguenza anche lo status di testimone si ridefinisce.

Oggi, di fronte al conflitto in Ucraina e al genocidio del popolo palestinese, per la prima volta si è introdottə ad una conoscenza diretta de i massacri, le implicazioni e le responsabilità.

Con Alessandro discutiamo della necessità o meno di dichiarare il luogo di provenienza delle clip. Ci interroghiamo sul come si possa inserire un lavoro che utilizza immagini di luoghi in cui vi è un conflitto attivo, in un contesto storico-sociale in cui la guerra è dichiarata e dichiarante.

In Senza titolo (Tonante veduta) clip di cieli, alberi, albe si susseguono scanditi dal suono delle bombe. Sono immagini non riconducibili ad un luogo specifico, che si fanno universali. Soggetti politici che, quando posti all’interno di uno schema compositivo, assumono la forma ulteriore di superficie pittorica.

Alessandro riconosce e cerca nell’immagine trovata un valore estetico, riconducibile alla categoria del perturbante. Effetti di spaesamento possono essere ottenuti quando chi osserva è posto al cospetto di una ripetizione continua di una stessa situazione. La ripetizione visiva della tragedia a cui assistiamo quotidianamente può portare ad una duplice reazione. Se da un lato potrebbe innescarsi un processo di derealizzazione, dovuto ad una incapacità di riconoscere la realtà che ci viene sottoposta, dall’altro l’immagine potrebbe agire a livello di simulacro, scaturendo reazioni riconducibili all’ambito corporeo, reali. Per simulacro si faccia riferimento alla definizione di Lucrezio, che nel De rerum parla di sottili veli atomici che si staccano dalle cose e che appaiono come del tutto identici alle cose del mondo, i quali, venendo a contatto con i sensi dell’uomo ne determinano le percezioni.

L’operazione di Manfrin consiste nel recuperare materiale per comporre un oggetto che, nel suo aspetto poetico, pone il focus sulla complessità del ruolo dell’immagine, in un contesto in cui quest’ultima è il più diffuso mezzo di informazione e formazione del pensiero individuale e collettivo. Di per sé in Senza titolo (Tonante veduta) si produce un’immagine ulteriore, che mostra l’ampiezza delle possibilità di percezione e fruizione.

Come tipicamente accade nei lavori dell’artista, anche qui vediamo convivere più livelli di riflessione, tra voyeurismo, pittura naïve e la tragicità di un confine bombardato. Manfrin, allora, con il suo lavoro forse ci introduce nelle possibili stratificazioni di un’immagine e le sue implicazioni.

Con Senza titolo (Tuonante veduta), si introducono questioni quali la lettura della rappresentazione del contemporaneo, il ruolo dell’individuo - e nel particolare dell’artista - in un contesto critico, in cui l’informazione si compone di immagini liquide e, infine, mostra il valore poetico e politico della documentazione amatoriale.

Alessandro Manfrin ci pone in una condizione di disorientamento, rendendo visibile la soglia tra distacco e un’empatia incorporata, tra tragedia e desiderio. In questo spazio c’è la possibilità del dubbio, non di certo

nei confronti della postura politica del lavoro e di chi lo ha concepito, ma piuttosto circa la percezione che si ha dell’immagine, le modalità di reazione dell’uomo di fronte agli eventi iconici. Il dubbio in questo caso sarà da intendersi come un esercizio contro il sopore della critica, verso l’iperbole, dove il linguaggio poetico si fa ponte e tramonto.

(en) Blueback

Text by curator Giulia Menegale

For his solo show at Platea, Alessandro Manfrin exhibits a series of advertising posters recovered from the city, overturned and reassembled as if they were a sky where the viewer’s gaze is destined to get lost, disoriented. Through this operation, the artist leaves the blueback paper of the posters uncovered. Blueback is a material used in advertising signage, in order to cover the underlying posters when new ones are put up, preventing the images printed in each layer from interfering with each other. Now torn, now rolled up and abandoned on the ground. These materials fascinate the artist because of their ability to retain traces of urban life. The frenetic pace of the contemporary city appears transcribed in crusts and ripples of these advertising posters even before the artist collects them to transform them into the wallpaper that covers Platea’s room, now in its entirety.

The advertising posters are subjected to constant change on city’s billboards, under habituated eyes of those who inhabit it. The city that Manfrin portrays is Milan, the place where the artist lives and which is the subject of many of his works prior to those exhibited at Platea. The artist describes Milan starting from those objects that he himself describes as ‘exhausted, tired’. Disused billboards are in fact objects that have lost their ability to attract attention of those who pass by them. Piled up by roadside, the skeins of blue backgrounds are perceived by the artist as the shell of an urban unconscious deprived of its natural ability to produce new desires. Through his wanderings, Manfrin is interested in “tracing scars of acceleration” linked to “a hypertrophic consumerism” that reproduces itself at various levels of urban reality - through people who inhabit it, as well as through the life cycle of objects. In this sense, blue back cards exhibited by the artist at Platea are a skin. The viewer is placed in front of an image of the skinned body of the city of Milan, without any mediation.

The artist collects the advertising posters and then spreads them out under a press, improvised in his Milanese studio. Working in this way, Manfrin makes these torn posters into smooth sheets ready for reuse. At Palazzo Galeano, the blue back papers taken from Milan entirely cover interior of Platea in an unusual position compared to how they are normally hung in cities. Indeed, the advertising images, of which the blue backs embody the back, or the background, are no longer accessible to viewer’s sight. Manfrin performs this action of a reversal of levels, between blueback paper and advertising print, imposing an abundant degree of abstraction on the final image that the artist presents during his solo exhibition. Thanks to the refined effect of almost total overlap between walls of the space and the material used, the perimeters of Platea’s walls limit and compress the potentially boundless and horizon-less vision generated by blue of the paper used. “Blueback” therefore manages to bring together, on the one hand, the attempt to transform into a vision the acrid and unhealthy smell of the city that the artist introduces to Platea with this work and, on the other, the romantic and poetic imagery of “Il un cielo in una stanza”, as the popular refrain of Gino Paoli’s song goes.

The action proposed by Manfrin differs from practices that could be considered similar -among them, one can cite historical examples, such as the Situationist détournements, or the practice of the flâneur of Benjaminian memory, among others- in that it assumes a posture towards the city that is neither rejecting and moralistic, nor does it correspond to a total sense of ecstatic abandon and fascination. The urban landscape is described in the artist’s works through a layering of the multiple places and temporalities that characterise it, now fused into a single image. This is the result of Manfrin’s crossings of the city, during which the artist’s subjectivity is silenced without ever being completely absent. Posing as a collector of urban materials, the artist shows us the spontaneous poetry generated through the use, consumption and finally abandonment of the city’s common objects.

GIULIA MENEGALE: With Deborah, we had wondered about the process of listening to an artwork. She spoke of the concept of threshold relative to Platea's window, what will you tell us about? ALESSANDRO MANFRIN: I envisioned my work for Platea as an environment in which you can dive with your eyes, while your body stays back. The idea is to make one's gaze float on this image. There is no invitation to enter, it is an open door on this vision. "Blueback" is an image which one encounters. MARCO SGARBOSSA: In your work you spread your blueback paper on all the surfaces of Platea’s walls, including the ceiling and the floor. This image makes me think of a sky, a sky which, however, has corners. AM: I am trying not to use the word sky in the narrative of my exhibition. Though, on the one hand, it appears to be the first thing you perceive when you look at it, on the other, the image of a sky does not fully exhaust what this work is about. This is an image made from waste materials produced by the city. Blueback paper tastes like asphalt, it tastes like rain. This sky we get lost in with our gaze, it is a sky made of materials which tell the story of an extremely tired and dirty urban context. MS: So one could say blueback paper creates a vision which is not clean in the broadest sense of the word. By looking at these sheets of paper, we find that they form irregular patterns. Maybe they're random, maybe they're not. AM: We are looking at an image which hasn't been painted. I take materials which no longer belong to anyone. They exist in a limbo of belonging. My role is simply to steal them and bring them to Platea, but I don't interfere by making them more or less sky, more or less dirty and so on. It's the sheets of blueback paper which somehow speak. SG: That of an indoor sky? AM: An indoor sky. LUCA TREVISANI: Does the focus of your work lie in the construction of a space with all its rules-like the ones you’ve just shared with us-or in the poetry and romanticism of Gino Paoli's "Il cielo in una stanza"? AM: It's the encounter between these two approaches which interests me. On the one hand, there’s the seductive power of the poetry of this material, and on the other, there is an analytical focus on what the matrix of this material really is. Billboards are an extremely distinctive and rigid material which follows the rules of the Western capitalist city. But they are also the material which now gives shape to this very room, here at Platea. MS: You said you would not like to use the word sky to describe your work. Would you like to use the word "capitalism" instead? AM: I think so. The sky is the first aspect which emerges from the encounter with my work. In addition to this element, I would also like to tell what blueback paper is and how it fits into a hypertrophic city, such as Milan. DEBORAH MARTINO: With your work, you bring the medium on which the billboards were printed inside the space of Platea. It's as if you were flaying the city, giving its skin a new shape within the display window. AM: What you are saying is definitely present. I take the city's skin and turn it into another casing. In some way these are materials which come from the city's organs, from the underground. Inside this window, they turn into a sky. So my intention is not only to move the materials from one place to another, but also to have them emerge from below, from the dirt. From the asphalt, where I find them. From Milan's stations, where I rip them out. Assembled in this way, it seems to me that they partly disappear. They become a kind of visual white noise, occupying the space by hardly occupying it at all. DM: It’s as if you were expanding the walls of Platea, tearing them down. LT: Alessandro says he is stealing the materials, but I am not sure if that is really the case. For instance, what is an advert once it expires? In my opinion, it is an object which has no clear status, and no clear owner. You, Alessandro, take these types of objects and redevelop them in a very strange way. AM: So far, I have used the term stealing a lot. Maybe because I associate it with how I feel when performing the physical action of taking these objects, with gloves on, and walking away with them, in secret, at night. When I take these materials, I wonder what world they belong to at that point in time and why I might or might not take them. Collecting these materials is above all an exercise in recognizing them, in finding them around the city, in encountering them. I don't think this work is about wanting to redevelop the material in the strict sense. It's rather about moving it into a new space. That cloud with the sky which doesn't belong to anyone can actually be seen, as it is, in the city, in the skeins of blueback paper abandoned along the streets. At Platea, this cloud acquires a relationship with the gallery space, with a new context surrounding it. MS: Stealing involves a change of ownership. You, on the other hand, are dealing with a no man's sky. DM: Is your performance therefore a gift? A gift from the city to you, which you then return to someone else? AM: More than gifts, I always thought of these scraps as the dots and commas of the city. And as such they were part of the narrative of the urban space. LT: If there is a gift, like Deborah says, then your work is a contradictory and complex gift. 'Blueback' is literally a gift made of rubbish. AM: It is a gift, sure, but it’s a gift that needs to be somewhat acknowledged. You must decide that it has become a gift, or else it remains rubbish, a by-product, a splinter produced by the city. When I carry blueback paper, it stinks. The material I use has been in contact with urine, smog, the recent heat, the humidity of the rain. The erotic attraction mentioned earlier too comes from the fact that I feel both attraction and repulsion towards these materials. When I load them into my car or carry them on the underground to my studio, I am perceived as a fool for going around with a piece of rubbish. I take care of it as if it were something that must get home safely. DM: How do you position yourself relative to work and the urban context? Is your work a reflection of how you feel within the city? AM: These scraps are a series of spontaneous sculptures. Small, involuntary poetic gestures that are reproduced throughout the metropolis. I don't know how much I resemble them. I think these materials tell the identity of the urban context in which I now live, Milan. MS: What piece of art is not, even in the slightest bit, autobiographical? You clearly don't live in the countryside if this is the kind of work you produce. AM: Of course, I see these materials as a portrait of the city I live in and in which my body fits. They're a part of the routes I take on a daily basis. That being said, my work is closer to a portrait of the city than it is to a self-portrait. GM: How do I know you didn't get those billboards from a village in the countryside? Or from a town other than Milan? AM: Of course the notion of waste exists in the countryside as well as in the city. I believe it's the pace which makes the difference. It's the amount of waste that changes from the city to the countryside. My work feeds on this hyperproductivity of the city. This is why I would not be able to work the same way if I lived in the countryside. The more waste the city produces, the quicker my work gets. LT: What will you do with these billboards once the exhibition is over? AM: I would like for them to remain crystallised forever. During the Platea period this crystallisation will be visible. I don't know if I will then fold them up and put them away, in a drawer. This remains to be seen. GM: That's your collector's side emerging... a fetish for the object. AM: Sure, there is a fetishism in collecting these objects. But when they stop being objects and become work, the fetishism fades away. The space at Platea allows me to establish a certain distance between the blueback paper and the spectator. These objects should not be observed with a magnifying glass, as if they were spectacular fossils produced by the city. GM: Is it a full window display, or an empty one, the one you exhibit for Platea? AM: Perceiving this space as empty can make you feel even more suspended. I chose not to have anything inside the space other than this material because I'd like people looking at this window to experience the instant you're about to fall, when you have nothing left under your feet. That emptiness is what I am after.

(en) Habitat. The relational space of being. Simondi Gallery

Text by Lucy R. Lippard

[...] Multidisciplinary artist Alessandro Manfrin’s sound sculpture Quintetto (2022), consists of five metal pipes found in his daily wanderings around city streets, seeking his materials – “shards

of thought serving as the city’s punctuation. Things given to all and belonging to no one, not quite waste, suspended in limbo, awaiting judgment.” The pipes are laid out in a flowing form. Next to this abstract sculpture, connected by electrical cables, is its technological twin – the Dolby Surround 5.1 system paraphernalia that animates it, amplifying sounds sampled in subway stations. The two dissimilar forms collaborate to communicate the artist’s message in a particularly contemporary manner. He calls it “a sort of organ that brings together the ethereal and the urban.” [...]

Text by Francesca Simondi

[...] Two installations open the exhibition in the guise of a portal to walk through, leading us to a “suspended place of being,” real, concrete but, at the same time, abstract and utopian. A deep echo envelops the exhibition space as if it were a call, a vibrating shock from the underground. Solo (2023) by Alessandro Manfrin, is a sound sculpture, a metal pipe that blends into the architecture of the gallery, spreading the sounds recorded in the metro stations into the space. [...]

Dreams, the theme that will guide the next edition of Post Scriptum in 2025, are also evoked in the title of Alessandro Manfrin’s series Hard Work Soft Dreams(2023), which opens and closes the exhibition path of this show.

The mattress is that intimate place where we sleep, make love, dream, sometimes play, die, cry. Many artists have narrated this intimacy, among the most touching are Untitled (1991) by Felix Gonzales Torres, My Bed (1998) by Tracey Emin, and the shelters for the homeless designed by Michael Rakowitz for the ParaSITEproject (1997). In his Hard Work Soft Dreams, Alessandro Manfrin recovers used mattresses from the urban space, belonging to the intimate and private sphere of strangers, and photographs them integrated into the city, wrapping them around the corners of buildings, laying them on sidewalks and house walls. “Hard Work Soft Dreams is a shared public space” – Manfrin explains – “A space that leads to reflection on the role of dwelling within contemporary cities and at the same time creates a disturbing urban landscape due to the very nature of the material.

The title of the work recalls a sort of slogan typical of the rhetoric of capitalism and personal success, an invitation to hard work and soft dreams”.

(it) Intervista all'artista Alessandro Manfrin per Artribune. Saverio Verini

Per Alessandro Manfrin le città contemporanee sono corpi esausti, consumati, fragili. Attraversando lo spazio urbano, l’artista ne raccoglie schegge e umori: cartelloni pubblicitari, immagini legate a cantieri, piante che si impossessano di edifici in disuso, suoni della metropolitana. Un’atmosfera fantasmatica pervade le opere di Manfrin. Difficile incontrare figure umane nei suoi lavori; e, quando questo accade, si tratta di immagini provenienti dalla fine degli anni Sessanta, quasi degli spettri. A pensarci bene, Manfrin sembra mettere in scena il ricordo sbiadito di una città, in cui temporalità differenti rendono complicato capire a che punto cominci il passato e termini il presente. Lo sguardo dell’artista è rivolto all’asfalto che calpesta così come alle cime dei palazzi che svettano nei luoghi dove vive, costantemente alla ricerca di tracce da cui partire per la realizzazione di interventi che somigliano a monumenti precari e incerti. Manfrin vuole cogliere il potenziale poetico e lo struggimento che possono derivare dall’osservazione del contesto urbano, rinunciando tuttavia a ogni intento consolatorio e, al contrario, sottolineando i limiti dei luoghi che abitiamo.

Saverio Verini: Nel 1863, Charles Baudelaire individuava in Constantin Guys il pittore della vita moderna, capace di esaltare la velocità e il fermento che attraversavano una città come Parigi in quel periodo. A distanza di 160 anni anche tu ti soffermi sulla realtà urbana contemporanea, offrendone una lettura di segno apparentemente opposto.

Alessandro Manfrin: Mi piace pensare di condividere con Constantin Guys una certa attitudine da flâneur e un’attrazione nei confronti degli “effetti collaterali” che le città contemporanee producono. Penso che la città e i suoi ritmi siano, nel mio lavoro, un pretesto per parlare di abitare, e quindi per parlare dell’uomo. Il contesto urbano è una piattaforma dove il privato e il pubblico si mescolano e si confondono. Sull’asfalto e sui marciapiedi si trovano costellazioni di oggetti abbandonati, consegnati a tutti e appartenenti a nessuno. La città contemporanea è l’habitat ideale per il proliferare di rumori bianchi e scarti, come fossili senza storia né tempo. Lavorando al progetto Blueback, esposto a Platea Palazzo Galeano, a Lodi, l’idea era quella di partire dall’ultimo anello di questo sistema nevrotico e iperproduttivo, ovvero le pubblicità applicate sui billboards e, con il retro di questi materiali, produrre un’immagine astratta, un “cielo in una stanza” fatto di immondizia destinata al macero.

SV: Nelle tue opere le immagini digitali (per esempio estratti di video trovati online) e alcune tracce del paesaggio contemporaneo (penso ai pacchi delle grandi compagnie di spedizioni online) coesistono con elementi che rimandano a un passato più o meno recente (immagini di cortei degli anni Sessanta e Settanta, architetture nate nella seconda metà del '900...). Anche formalmente, trovo che ci sia una relazione con certe pratiche artistiche affermatesi negli scorsi decenni.

AM: Quando penso a un lavoro è difficile prescindere dalla storia dell’arte o, perlomeno, dalla tradizione in cui il lavoro si inserisce. Come spiega George Kubler nel saggio La forma del tempo. La storia dell’arte e la storia delle cose, l’arte è prima di tutto materia che si stratifica al tempo geologico della terra, e questo per me vale anche quando lavoro con immagini prelevate online o con immaginari legati alla memoria collettiva come quelli degli anni Sessanta e Settanta. Se dovessi tracciare una linea di esperienze della storia dell’arte che accompagnano i miei pensieri quando lavoro, sicuramente inserirei tutta la tradizione del Romanticismo, a partire dalle rovine incise da Piranesi, passando per i ruderi e i paesaggi dipinti da Friedrich per arrivare alla scultura-tempo di Robert Smithson e ai paesaggi urbani di Cyprien Gaillard.

SV: Che rapporto hai con la storia, a partire da quella dell’arte? In che modo cerchi di aggiungere qualcosa di tuo o comunque legato al tempo che stai vivendo?

AM: Non c’è uno sguardo nostalgico nei confronti del passato, la serie di lavori sulle architetture di Milano (Milano palazzi) mette insieme architetture iconiche della seconda metà del ‘900 con il cantiere della nuova sede della palestra Virgin. In questo caso mi interessa lavorare sull’idea di facciata, e la città contemporanea mescola architetture brutaliste con palazzi di vetro fragili e precari o, ancora, superfici ricoperte da piastrelle conquistate da edere e muffe.

SV: Utilizzi spesso pacchi postali o contrassegnati dai loghi delle aziende di commercio online: è un semplice riferimento a un oggetto ricorrente della nostra quotidianità o c’è una qualche intenzione critica nei confronti della società contemporanea?

AM: I pacchi da spedizione mi interessano perché registrano le tracce dello spostamento. Viaggiano e si muovono, la loro funzione è quella di proteggere oggetti e desideri. Il lavoro untitled (from a to b) è un autoritratto: sono registrazioni del mio respiro che vengono riprodotte da uno speaker che dura per giorni e che viene spedito dal luogo in cui vivo allo spazio in cui viene esposto il lavoro. L’idea è quella di far passare un oggetto tanto etereo ed effimero come il respiro attraverso mani sconosciute; mi piace pensare che tra i pacchi che vengono smistati ce ne sia uno che custodisce la registrazione del mio respiro. Nel caso della serie untitled (domestic plants as a scultpures) i pacchi assumono la funzione di basamento. Quando ho realizzato quei lavori pensavo alle sculture di Brancusi e ai plinti che diventano scultura. È come se la pelle di questi lavori tenesse conto delle botte dovute dagli spostamenti, ma anche che sia testimonianza di tutti quei loghi che regolano le leggi di mercato in cui viviamo e in cui il mio lavoro cerca di inserirsi, producendo piccoli cortocircuiti.

SV: Non hai ancora 26 anni, ti sei appena affacciato al mondo dell’arte. Quali opportunità e, insieme, difficoltà ti sembrano prospettarsi? Hai uno studio? Come riesci a pagare l’affitto?

AM: Ho avuto uno studio per circa un anno che ho lasciato da poco, ne sto cercando un altro, sono in quella fase in cui desidero tantissimo uno spazio in cui poter lavorare ma devo fare i conti con le muffe degli scantinati e i prezzi folli di una città come Milano. A settembre del 2021 ho iniziato a collaborare con la Gian Marco Casini Gallery di Livorno, sono molto contento dello scambio che stiamo avendo. In questi anni ho lavorato anche come assistente per altri artisti, ma sto cercando di dedicarmi esclusivamente al mio lavoro. Mi piacerebbe fare una residenza all’estero, soprattutto per vedere cosa succede al mio lavoro se cambio la città in cui vivo. In Italia sembra difficile pensare a lavori più complessi da sostenere, ho in progetto di realizzare altri ambienti come Blueback, non credo sia impossibile farlo qui, ma sento che potrebbe farmi bene respirare l’aria che sta fuori. Penso che l’arte sia prima di tutto un pretesto per interessarsi a qualsiasi cosa: è un linguaggio che si ridefinisce costantemente e anche il sistema che lo alimenta, con tutte le sue criticità, ha la capacità di autosabotarsi e rigenerarsi di continuo.

(en) Statement

Wandering through the city’s neighborhoods as a daily practice. Recognizing shapes and objects on the roadside: construction debris, posters, furniture, beds, mattresses, clothing. Objects waiting for the sanitation department to take them away. The city of the contemporary human and its infinite waste, fossils even before time fixes matter. Tired, worn-out objects bearing traces of unchecked consumerism, and small poetic gestures as well. Urban subconscious. Cerulean mattresses with white and silver embroidery, roughly rolled up and laid out on the asphalt, as city fumes turn them into grey clouds. Adverts printed on blueback paper, once hung on billboards, become blue skeins, unintentional sculptures. Broken windows, beers, small monuments to life lived. Shards of thought serving as the city’s punctuation. Things given to all and belonging to no one, not quite waste, suspended in limbo, awaiting judgment. Dried-out plants in empty offices, ads for seasonal workers. Infinite and countless fragments of the neurotic and exhilarating race toward nothingness. Involuntary collection. Walking in the city becomes a game of tracing the scars of acceleration.

My practice is strongly multidisciplinary and includes different media like photography, sculpture, sound, installation.

(en) Tous les hôtels où je pourrais dormir ce soir, mais je dors là

Text by curator Chloé Poulain

It all starts with Perec, who in Espèce d’espace wonders whether moving the bed into a room changes the room. What does it produce?

Francesca tells me that for her, the bed is the real space, even more than the bedroom. The bed or the bedroom, as you prefer, is the central element of the last event in this cycle of exhibitions. The sheets like blank pages, the bed becomes a residual space for narcoleptic writing, in its mists sources and contexts merge and intermingle. The result is an agglomerate from which we can recognise certain bits of conver- sation or texts we’ve read. A long space into which the tired body slips. Further into the room, at the edge of the room, wedged in the window frame, a few papers are held up. List of hotels and places to sleep in the surrounding area during Alessandro’s stay in Paris. On metro tickets, till receipts, exhibition tickets. The accumulation of their fatigue over the sum of their consumption; in the cracks of this indefinite space, somewhere between what is temporarily Francesca’s place of life and work, and the rue de l’Hôtel de ville.

It ends with these few words, in a sleep deeply rooted in the fabric of everyday life.